Despite having attained self-sufficiency in the development of cryogenic engines to cater to the needs of the space sector, India has not achieved much success in the development of jet engines. It remains a critical gap that has hampered the indigenous fighter jet programme and needs to be addressed in mission mode

India’s jet engine development programme has been a long and challenging one with limited success till date. It’s a story of perseverance and determination. India’s jet engine development paradox revolves around the nation’s strong aerospace ambitions, clashing with the challenges of creating stateof-the-art technology in a field that demands expertise, innovation, research and immense resources.

India, despite its push for self-reliance in critical technologies, including cryogenic rocket engines, has not been able to develop a jet engine for its fighter aircraft.

There has been a long struggle to develop an indigenous jet engine despite having a significant aerospace industry, a large pool of skilled manpower and huge domestic demand. Till date, India has relied heavily on imported engines, notably from Russia, the US and UK.

India made its first attempt in the 1960s but a serious programme was launched only in 1989 with the GTX 35VS Kaveri engine development programme. Subsequently, in 1990, India collaborated with Russia to develop the Sukhoi/ HAL FGFA engine; however, the project got cancelled later. In 2010, the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) programme was launched for the indigenous fifth generation combat aircraft with an indigenous engine.

To meet the immediate requirement of engines for the LCA (Light Combat Aircraft) project as well as to bridge the technological gap, India has signed collaborative agreements with US firm General Electric (GE) and French firm Safran.

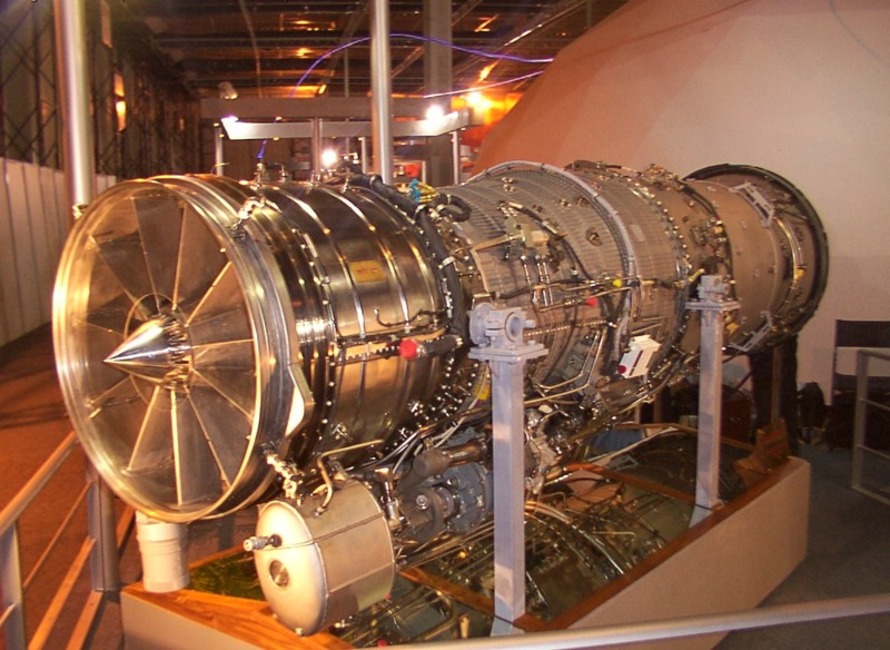

Recently, India made significant progress in engine development with the Kaveri engine being cleared for in-flight testing for the unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), like Ghatak developed by the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), Aeronautical Development Establishment (ADE), and Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE)—all Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) establishments. The successful development of the Kaveri engine could pave the way for future integration into more advanced fighter aircraft.

The science of jet propulsion is a highly complex and demanding technology that has been mastered by only four countries, notably the US, Russia, France, and UK. A fighter jet engine, being a most complex piece of engineering, is the heart of an aircraft requiring great thrust, agility and combat performance. It calls for expertise in aerodynamics, thermodynamics, and material science.

Concept simulations and wind tunnel testings are used to validate initial design specifications. Advanced materials are employed like titanium alloy, single-crystal super alloys, and ceramics developed to withstand extreme performance characteristics with temperatures reaching close to 2000°C.

Each major component of the engine like compressor, turbine, nozzle, and combustion chamber is meticulously designed and tested.

Once the initial development of the desired engine is achieved as per design specifications, a prototype engine is developed. The prototype undergoes rigorous ground and flight testing for validating its performance, reliability and safety. It is subjected to extreme altitude, temperature and combat conditions.

There are several compelling reasons for India’s jet engine paradox. Besides the complexities involved, the lack of infrastructure for design, testing, and advanced metallurgy has hampered the progress in this field.

The lack of clear-sighted leadership from the beginning in this critical area of aerospace development has been confounding. Brain drain of specialised talent to greener pastures like the US and Europe also did not help India’s ambitions. Finally, engine development is capital intensive with a long gestation period, which for some reason was not a priority area for India’s defence production planners and decision-makers.

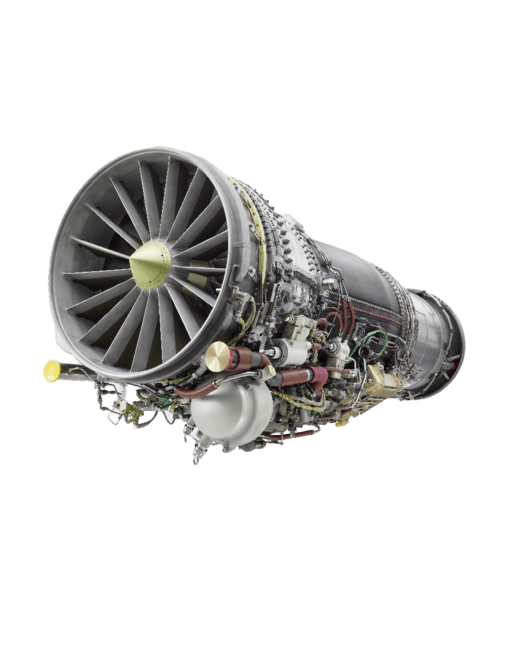

India is betting on domestic manufacturing of the GE F 414 engine (above) under a transfer-of-technology agreement with the US and on the DRDO’s Kaveri GTX-35VX engine, which has been under development for close to three decades, to drive its aerospace programmes

Safran and DRDO will co-develop a jet engine for the AMCA under the India-France Aero Engine Co-Development agreement

The kind of success the Indian space industry has achieved, has unfortunately not been achieved in the aerospace sector. This is one of the biggest contradictions that has existed in India’s advanced engine manufacturing sector for decades

Recent developments on this front have involved both indigenous efforts and collaborations worked out with friendly countries. Despite the daunting nature of the task, indigenous initiatives include the Kaveri engine—an initiative of the Bengaluru-based GTRE—which has been under development since the late 1980s. It has encountered numerous problems over the years; however, recently it has tasted some success wherein it has been cleared for the air test at a facility in Russia. This engine was initially planned to be utilised for the indigenous UCAV before its improved variants could be used in India’s AMCA programme.

The second active indigenous programme is the development of the 25 KN turbofan HTFE-25 by the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL). This engine is intended to be used in single-engine trainer jets, business jets and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs).

Two engines have been produced and are at present undergoing trials and further improvements.

The lack of involvement of private players in indigenous engine programmes has also contributed to the glacial pace of progress. The primary private player actively participating in the jet engine development is DG Propulsion, which has designed and built jet engines like the J20, the J40, and the J60 variants for UAVs. Other Indian defence sector companies like Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL) and Mahindra Aerospace are yet to establish themselves in the jet engine sector.

India’s foreign collaboration for jet engine development is in the form of signing some notable agreements with US, Russian, French, and UK firms. India-US collaboration for the GE F 414 engine was inked during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s last state visit to the US. Under this agreement, Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL) entered into a $716 million deal with GE for transfer of technology for manufacturing 99 GE F-414 engines for its indigenous fighter, LCA Tejas MK-ll. This engine is a turbofan engine that has been used by the US Navy for more than 30 years. It is equipped with dual-channel full authority digital engine control (FADEC), a six-stage high pressure turbine, and a fueldraulic system for nozzle area control.

The J60 is the only engine that has been developed by the private sector

It offers exceptional throttle response, excellent afterburner thrust and stability and unrestricted engine performance. The F 414 engine holds great significance for the LCA Tejas MK-ll programme as it is a strategic decision to overcome the present major gap in India’s indigenous fighter aircraft development programme, bogged down by the non-availability of a suitable locally made jet engine. Once the production of F-414 engines starts in the country, they may be utilised for the AMCA programme as well. This agreement is a significant component of the Initiative on Emerging and Critical Technologies (iCET) deal with the US. However, this deal has got delayed and has run into rough weather with cost overruns during the technical discussions between HAL and GE representatives.

India-France Aero Engine Co-Development is another significant initiative by the Indian government. Under this programme, the French engine company, Safran, will collaborate with DRDO to develop a new engine for the AMCA. This collaboration aims to bring the expertise in both countries together for a state-of-the-art power plant that will meet the future requirements of the Indian Air Force (IAF). This programme is different in the sense that it involves transfer of technology, including design, development, certification and production. This engine is expected to be a significant improvement over existing engines with advanced features and capabilities that will give the IAF a significant edge in combat operations.

The cooperation extends to various aspects of defence technology, including the joint development of combat aircraft engines and industrial cooperation for heavy-lift helicopters under the Indian Multi Role Helicopters (IMRH) programme. This collaboration has the potential not only to meet the immediate requirement of the AMCA programme but also to greatly help India’s engine indigenisation programme, thereby revolutionising the Indian aerospace industry.

India-Russia collaboration has a long history in the overall defence cooperation history of India. However, there have been few significant collaborations in the joint development of jet engines. Both countries are currently collaborating for the joint production of the Sukhoi fighter jet engine, the AL-31FP engine.

This partnership aims to increase India’s self-reliance in defence technology by locally producing these engines rather than solely importing from Russia.

HAL has recently signed an agreement with the IAF for the supply of 240 engines for Sukhoi 30MKI aircraft. This collaboration would also pave the way for future upgrades to the Su-30MKI fleet with newer engines. Russia has also offered its advanced ODK Kalimov.

110 KN engines for India’s fifth generation fighter programme. These engines are known for increased reliability, versatility, and efficiency. This Russian offer is with an aim to keep Americans away from India’s future fighter aircraft development programme.

The UK too is keen to establish a relationship with India in this critical area. But globally, the UK is a major player in the jet engine market, especially advanced military jet engines. Recently, during the second India-UK 2+2 foreign and defence dialogue in New Delhi, the UK delegates expressed strong support for Rolls-Royce’s proposal to associate with India’s AMCA fighter aircraft programme.

India, post-Independence, has remained a marginal defence and aerospace manufacturing country due to various reasons, including a highly questionable policy of not developing major indigenous defence industries. The country remained heavily dependent on foreign vendors for almost all its major defence equipment, including aerospace, so much so that it achieved the ignominious tag of the world’s largest importer of defence hardware.

However, in the past decade, India under its Make in India Atmanirbhar Bharat programme has received a significant policy and resource boost for indigenous defence production. The kind of success the Indian space industry has achieved, has unfortunately not been achieved in the aerospace sector. This is one of the biggest contradictions that has existed in India’s advanced engine manufacturing sector for decades.

However, with the current focus of the government, both through domestic collaborations as well as foreign government-to government collaborations with foreign jet engine manufacturers, the future looks promising for the aerospace sector. If these glitches in these collaborations are ironed out, India could well be on its way to joining the exclusive club of countries that have developed capabilities to manufacture fighter jet engines.

Add Comment