India’s stand on the suspension of the IWT, triggered by the latest round of bloodshed in Pahalgam, is one of the most effective non-kinetic responses to Pakistan’s refusal to clamp down on terrorism

Ambassadors of European nations emerge from the South Block after a meeting with officials of the Ministry of External Affairs

The agreement allocated the three eastern rivers— Ravi, Beas and Sutlej—to India, and the three western river —Indus, Jhelum and Chenab—to Pakistan, while allowing for limited use by each country of the other’s designated rivers under specific conditions. Despite wars, skirmishes, and the ongoing state of hostility displayed by Pakistan towards India, the treaty survived

For decades, the Indus Water Treaty (IWT), determining the water sharing formula of the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers between India and Pakistan, has provided not only life sustaining water to the people on either side of the contentious border, but also survived three wars—in 1965, 1971 and 1999—that India has been forced to fight against its belligerent neighbour.

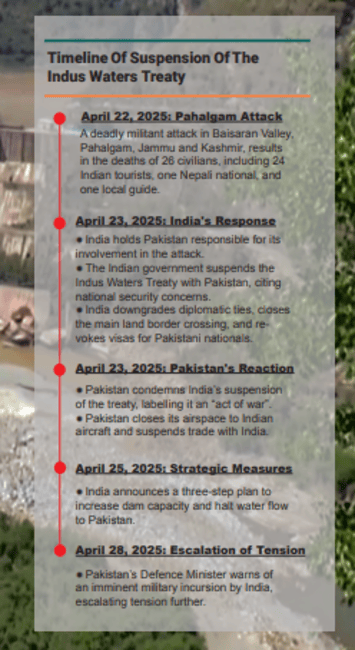

But on April 23, 2025, the Indian government announced it was putting the IWT in “abeyance” in response to the ghastly terror attack on Hindu tourists by Pakistan-based terrorists in Pahalgam the day before. This means that India will no longer abide by the terms of the treaty, mediated by the World Bank, that was signed in 1960 between Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan President Ayub Khan.

The horror of the targeted killings by terrorists shocked the conscience of the nation to such an extent that it forced the hand of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led Cabinet Committee on Security to take the drastic step. In 2016, Modi had already expressed his anguish in response to the terrorist attacks on a part of the brigade headquarters in Uri on September 17 that year. “Blood and water cannot flow together at the same time,” said Modi after the attacks claimed the lives of 18 soldiers.

The agreement allocated the three eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas and Sutlej—to India, and the three western river —Indus, Jhelum and Chenab—to Pakistan, while allowing for limited use by each country of the other’s designated rivers under specific conditions. Despite wars, skirmishes, and the ongoing state of hostility displayed by Pakistan towards India, the treaty survived.

But the Pahalgam terror attack has turned out to be a bridge too far for India.

Rising Tensions And The Tipping Point

The road to the suspension was neither sudden nor unexpected. Over the past three decades, India has endured multiple confrontations along the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir. Pakistan’s refusal to address genuine concerns of cross-border terrorism, insurgent support, and political interference have repeatedly derailed bilateral dialogue.

Over the decades, non kinetic retaliatory measures, including economic sanctions, airspace restrictions, and a diplomatic offensive at the United Nations and other multilateral platforms yielded limited results. “This is not just about water,” Prime Minister Modi said. “It is about sovereignty, security, and justice. India cannot continue to reward Pakistan with goodwill while our people pay the price in blood.” The Pakistan Army and its intelligence arm, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)—a state within a state have not only lent active support to cross-border terrorism, they also orchestrate terror plans for various terrorist groups by providing logistical support, ammunitions, and covering fire during infiltration.

What The Suspension Means

India’s suspension of the treaty does not immediately translate into stopping the flow of water of the three western rivers to Pakistan, but it does pave the way for a rapid transformation of the water landscape in the region. First and foremost, India can now start building infrastructure like dams and diversion systems comprising a network of canals and tunnels on the three western rivers which have a combined flow of 133 million acre feet (MAF). According to the IWT, India can use 20% of the 133 MAF, while the remaining 80% must flow to Pakistan.

Apart from this, India won’t provide seasonal hydrological data pertaining to the three rivers to Pakistan, which it was obligated to do under IWT. This effectively means Pakistan will have a much tougher time in managing floods in the high-water season. The suspension also freezes India’s obligations under the mechanisms of dispute resolution. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs framed the decision as a “necessary measure” for Pakistan’s refusal to comply with anti-terrorism obligations under international law. Predictably, Pakistan reacted with alarm, calling India’s decision a “brazen violation of international law”. Pakistan has also signalled that it will protest against India’s decision at the United Nations Security Council. Nearly 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture is dependent on the Indus river system. Even modest unpredictability in water flows could have devastating consequences. Western Punjab and Sindh, considered the food bowl of Pakistan, will be dealing with the unpredictability of floods and droughts. As and when India develops suitable infrastructure on the Indus, Chenab and Jhelum, the flow of water into Pakistan will be completely within India’s control.

This extreme step seems to be India’s longterm strategy, as it will take, according to water management experts, at least two to three decades to come into effect besides a huge amount of capital investment.

Global Response

The United States under President Donald Trump has sent out confusing signals regarding its stand on this latest round of Pakistan sponsored terrorism, while China, a close ally of Pakistan and a major stakeholder in infrastructure projects in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK), expressed deep concern” over the treaty’s suspension. India has also turned down offers of mediation by foreign countries by stating that unless Pakistan stops its support to terrorists operating from its territory, there is no point in negotiating with a repeat offender. However, back channel talks to defuse the situation cannot be ruled out though they are unlikely to yield any results as, on April 29, Modi gave a “free hand” to the three arms of India’s military to decide the “time and place” for striking inside Pakistan in retaliation to the latest terror attack.

However, behind closed doors, diplomatic channels remained partially open. Back-channel talks in Muscat and Dubai suggested that India might consider restoring the treaty’s provisions if Pakistan took “verifiable steps” to dismantle militant networks. However, progress was slow, and mistrust ran deep.

The monsoon season will show the extent of impact of the denial of hydrological data to Pakistan. Heavy rains in the upstream regions—a regular feature during the Indian monsoon season—will lead to the swelling of rivers. In the absence of ground-level data, Pakistan is likely to face considerable hurdles in the storage and release of water from its dams and barrages in the western part of the country.

It is clear, however, that the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty marks a turning point in Indo Pakistani relations. It has exposed the fragile underpinnings of regional stability and reminded the world that even a seemingly apolitical issue like water can become a flashpoint when one neighbouring country makes terrorism an instrument of state policy towards another. This is the message that India should convey to the world in loud and clear terms.

The Pakistan High Commission wears a deserted look after the reduction in diplomatic staff

Add Comment