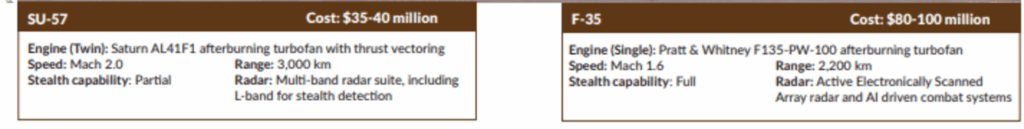

India’s defence planners and IAF top brass got the rare opportunity to compare both the Su-57 (left) and F-35 (right) side-by-side at Aero India 2025 that was held in Bengaluru in February

The fast depletion of the fighter fleet of the IAF due to the retirement of ageing aircraft has rung alarm bells. Both the government and the IAF must accord top priority to acquisition of fighters to meet immediate needs, while charting a clear path for developing indigenous capacity to service future requirements

The Indian Air Force (IAF) is seen extensively carrying out HADR (Humanitarian Assistance in Disaster Relief) missions within and outside the country, which not only draws praise for its highly professional work but also reinforces the importance of its operational capabilities.

The IAF’s fleet of advanced transport aircraft comprising C-17s and C-130s, and helicopter squadrons of Chinooks and Mi-17 V5s, have been discharging its strategic and tactical HADR role, respectively, in a commendable manner. Most recently, the IAF provided HADR support in Myanmar and Thailand after the devastating earthquake. However, the primary role of the IAF is to ensure security of India’s airspace. This can only be ensured through an effective fleet of advanced fighter aircraft. With its depleting fighter squadrons, unstable neighbourhood, unpredictable world order and the induction of fifth generation Chinese J-20 and J-35 stealth fighter aircraft on its northern borders, the alarm bells have started ringing for India’s national and regional aerospace security. To handle a two front war, the IAF is sanctioned a strength of 42 squadrons of fighter aircraft; however, due to the phasing out of the ageing MiG-21, MiG-23 and MiG-27, delayed procurement and delayed indigenisation, the fleet strength has depleted to just around 30 squadrons. The depletion in the fighter squadron strength is alarming for two reasons. Firstly, acquisitions take a long time due to reasons of availability, cost, indecision both at the service headquarters and the Ministry of Defence. Secondly, there is fast upgradation with advanced fighters in our northern and western neighbourhoods.

Lost Decades For IAF

The ageing MiG-21 fleet, being the largest component of the IAF’s fighter fleet, and the vintage Jaguar/MiG-29 fleet were planned to be replaced with a mix of the LCA, MMRCA and MRFA programme of local production as well as foreign acquisitions. The MMRCA (Medium Multi Role Combat Aircraft) programme involving acquiring 126 aircraft dragged on for years; it was finally cancelled in 2014 after the acquisition of 36 Rafale aircraft (two squadrons) from France. The emergency acquisition of two squadrons should have been followed up with faster decision-making on acquiring more Rafale squadrons through direct purchase or local production but that did not happen. Orders placed with Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL) for supply of the LCA (Light Combat Aircraft) Mk-1 and Mk-2 have been way behind schedule, complicating matters further.

The LCA project was conceived and started in 1983 to meet future requirements of the IAF and the Indian Navy. The project was designed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)’s Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) for manufacture by HAL. The LCA made its first flight in 2001 and entered into service in 2015. In due course, the IAF ordered 40 LCA Mk-1 aircraft and 83 Mk-1A aircraft, but supplies of both have been behind schedule. HAL has delivered two squadrons of the LCA Mk-1 but the Mk-1A has been extremely delayed primarily due to General Electric (GE) being unable to supply the contracted number of engines in the past two years. Finally, on March 26, 2025, GE announced that it had supplied the first of the 99 F404-IN20 engines to HAL.

This offers some hope that HAL will begin supplying the LCA Mk-1A aircraft to the IAF in the near future. However, dependency on a foreign collaborator for the engines will continue to be a big limiting factor until India attains self-sufficiency in this sector as well (read the February 2025 issue of The First Witness for a detailed analysis).

Fighters On Offer For The IAF

India’s future fighter procurement strategy could be a mix of indigenous capability and foreign collaboration. The IAF is quite familiar with the major fighter aircraft producing companies as a result of its evaluations for the MMRCA project. The IAF has dealt with Rafale, Gripen, and Eurofighter in the past. According to news reports, the front-runners appear to be the French Rafale, the American F-35 and the Russian Su-57—the last two even participated in the just concluded Aero India show at Bengaluru. A look at the techno-economic-strategic aspects of the three aircraft is in order to better understand the issue of selection for the IAF. The Rafale F4, a 4.5 generation fighter, with two squadrons of its earlier variant already in service in the IAF, becomes an automatic choice for an MRFA (MultiRole Fighter Aircraft). It is known for its agility and manoeuvrability with large payloads. It is considered more cost effective with lower operating and maintenance costs than the F-35. The Rafale offers full sovereign control over its operational parameters in comparison to the F-35.

However, how far the French government is willing to transfer technology for a Make in India initiative awaits clarity. Also, with Chinese fifth-generation fighters already in India’s neighbourhood, would the IAF and the Indian government be willing to go in for a 4.5 generation Rafale variant or prefer to stick with the existing Rafale which will be in service for the next three to four decades?

The F-35, a fifth-generation, multi-role offensive strike fighter, is a single-seater, single-engine (Pratt & Whitney F135-PW-100 afterburning turbofan) stealth fighter with three variants. It can achieve a maximum speed of Mach 1.6 with a range of approximately 2,200 km. It is equipped with advanced sensors including an AESA (Active Electronically Scanned Array) radar and AI driven combat systems. It has seamless data sharing capabilities. It comes in three variants—the F-35A, with a conventional take-off and landing for the air force, the F-35B, with a short field take-off and vertical landing for the marine corps, and the F-35C for the navy. As of date, the US manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, has already delivered more than 1,000 F-35s worldwide, including to the US Air Force. The F-35 has the advantage of a large global supply chain and extensive NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) interoperability. F-35s have proven their operational capabilities in the ongoing conflict in the Middle East. However, for India the fighter is beset with multiple concerns— its exorbitant cost (approximately $80 million to $110 million), tech transfer for its local production, American reliability in times of crisis due to complex software integration, and strict US export control regulations

As of date, the US manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, has already delivered more than 1,000 F-35s worldwide, including to the US Air Force. The F-35 has the advantage of a large global supply chain and extensive NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) interoperability

India’s indigenous fighters, the LCA Mk-1 and Mk-1A, have been inordinately delayed for induction due to GE’s inability to supply the engines on schedule

Additionally, India can continue with its indigenous fifth-generation, stealth AMCA development programme. The DRDO, responsible for the development of the AMCA, must fast-track its development with a judicious mix of Indian public and private sector companies

The Su-57, a reported fifth generation twin-engine (Saturn AL41F1 afterburning turbofan) fighter is Russia’s frontline defensive, air superiority fighter with partial stealth capabilities because of its reduced radar signature. It can attain a maximum speed of Mach 2 with an approximate maximum range of 3,000 km. It is highly manoeuvrable due to its twin engines and their thrust vectoring. It is also equipped with a multi-band radar suite, including L-band for stealth detection. The Su-57 is expected to be cost effective ($35 million to $40 million) in comparison to the F-35s.

The most favourable aspect for India could be Russian reliability during crises, operational familiarity, and economical cost with no operational limitations. Varying scenarios with a mix of indigenous development and international partnerships could make good the shortages.

Scenario 1

Procure 114 Rafale aircraft from France as part of the proposed MRFA (Multi Role Fighter Aircraft) programme along with indigenous development of the AMCA (Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft). The Rafale, already in service with the IAF, offers proven multi-role capabilities with nuclear deterrence. This could be the most preferable path owing to IAF familiarity with tech, logistics and training.

The purchase of this number of Rafales would amount to about five squadrons, which would take care of the immediate shortfall in squadron strength. The purchase cost of so many Rafales could be an issue but with such large orders, India would be in a commanding position to leverage its strategic partnership with France and at the same time the deal would make huge business sense for the French government. Additionally, India can continue with its indigenous fifth-generation, stealth AMCA development programme. The DRDO, responsible for the development of the AMCA, must fast-track its development with a judicious mix of Indian public and private sector companies as well as foreign friendly collaborations. This approach would be a time-tested one, considering French reliability, while avoiding American unreliability, and fostering development of indigenous advanced fighter capabilities.

Scenario 2

Keeping in sync with the enhanced IndoUS strategic partnership, India could fulfil its immediate MRFA need with the US F-15EX, a 4.5 generation heavy fighter with advanced avionics, large payload capability and long-range strike potential, while continuing with an accelerated AMCA development programme. This scenario balances India’s immediate fighter shortages along with its interoperability with Quad partners like the US, Japan, and Australia.

Scenario 3

This could be a Russian option, which is time-tested but of late has witnessed inconsistent delivery schedule and cost overruns. India could meet its MRFA requirement through the Russian Su-35 or MiG-35 along with a few squadrons of the Su-57.

This option might ensure affordability, familiarity and timely delivery, but might attract US sanctions as well. A combination of the above measures is likely to ensure:

(a) Immediate induction of at least two squadrons of Rafale fighters.

(b) Commencement of the MRFA class fighter programme by 2027-28 to ensure the raising of five to six squadrons by 2032.

(c) Freezing of the LCA Mk-2 design in 2025 in order to start production by 2028- 29 to have six squadrons by 2035 as replacement for the Jaguars and MiG-29s.

(d) Prioritising of the AMCA development to have the first flight in 2028-29 and serial production by 2032-33. Securing of foreign collaborations for engines and stealth tech at the earliest.

(e) Aiming to start production of the AMCA by 2035 so that approximately five squadrons can be raised by 2040. In the interim, upgrading of the entire fleet of Su-30MK1 with AESA radar, EW suites and Astra MK2 missiles and strengthening force multipliers like combat drones, Aerial Electronic Warfare (AEW) systems, Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) and refuellers.

The Way Forward

In order to arrest and augment the falling fighter strength of the IAF, the government needs to put in place a few institutional mechanisms at the earliest. Decision-making should be at PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) level to avoid further bureaucratic delays in facilitating early delivery of the MRFA and AMCA class of fighters to the IAF.

The PMO also needs to look at the inability of GTRE (Gas Turbine Research Establishment) to produce engines as required for our fighter development programme and fix it without any further delay. The government should also restore HAL’s leadership to a senior IAF aviator for bringing synergy and creating a sense of urgency among different arms of HAL as is the case with naval officers heading shipyards.

Speed and efficiency in production and procurement should be a priority for HAL for the LCA Mk-1 and Mk-2 programmes.

Government-to-government deals need to be struck for the MRFA and FGFA (Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft) programme.

This can be done by encouraging public and private sector companies such as HAL, Tata, Larsen & Toubro, Adani, Godrej, Kirloskar, etc., to establish joint ventures with foreign companies like Dassault, GE and BAE for expediting the development and production of the MRFA and FGFA. The private sector should be involved in developing cutting-edge aerospace solutions in areas like stealth technology and engines. Also, minimising fighter diversity would help in easing supply, maintenance and training requirements thereby facilitating better serviceability status of the fighter fleet. Early freezing of design specifications for the LCA Mk-2 and AMCA programmes would help in kicking off early development of prototypes. This must be supported with adequate budgetary allocation.

For the government and the IAF, various options are available on the table. However, top priority must be accorded to fulfilling the immediate need for 114 MRFA from the French, Russian, American or European fighter options to arrest the slide in the IAF’s strike capabilities. Intervention from the top levels of government, including the PMO, is essential for ensuring faster deliveries of the LCA Mk-1 and Mk-2 to the IAF. The government needs to play a proactive role to remove the roadblocks that are hindering the delivery of engines for the two programmes.

At the same time, the development of AMCA should be fast tracked after identifying the stealth needs and engine partner so that the 2035 timeline for delivery can be strictly adhered to. There is a school of thought that advocates India opting for foreign fighters for both MRFA and AMCA categories in the light of HAL’s poor track record of meeting deadlines. At the same time, the breathing space could be utilised for developing capacities in critical areas. In no case should the IAF and the Ministry of Defence (MoD) repeat the mistake of the 1960s, when the indigenous HF Marut fighter development programme was jettisoned in favour of foreign aircraft, thereby giving indigenous development of fighters the go-by completely. The IAF leadership needs to be absolutely clear in putting up their case to the MoD with respect to the MRFA and AMCA and should pursue it relentlessly, irrespective of the change in guard with the passage of time. Lastly, the top political-bureaucratic leadership needs to keep in mind that no price can be too high for the ensuring of national security.

The government and HAL should learn the lessons from its LCA programme and ensure mistakes are not repeated in the development of the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft

Add Comment